Amyris’s breakthroughs in bioengineering--and its plans to make biofuels from Brazilian sugarcane--promised to transform how the world’s businesses produce energy, cosmetics, and medicine. Then reality (and Wall Street) got in the way.

The climb up the steel steps is dizzying--like ascending the tower of a European church, except the steps lead to a platform bolted to the side of a gleaming new chemical plant. Here in Brazil, under a brilliant blue sky, Eduardo Loosli, the plant manager, pauses to explain a vision of the future. "I used to manage a Molson Coors beer manufacturing plant, and it’s not all that different," he says, leaning on a railing and surveying the scene around us. Directly below is a cityscape of huge stainless-steel tanks. Out beyond the tanks, and stretching far into the distance, are dense greenfields of sugarcane.

Yeast turns grain into beer, Loosli says. Here, in this new plant, genetically engineered yeast created by the plant’s owners--the California biotech company known as Amyris--turns sugar into liquid fuel. At the end of the platform, Loosli points to two special "seed" tanks. "The yeast enters the system here," he says. When production starts, a glass flask of Amyris’s special strain will be poured into each tank, and the yeast will multiply until it becomes a thick, hungry broth. For two weeks, the yeasty stew chews up as much as 1.2 million liters of energy-rich cane syrup. The end product is farnesene, which can be adapted to a seemingly perfect replacement for petroleum-based diesel. Not only does farnesene-based diesel cut pollutants from vehicle exhaust pipes, but since it derives from cane syrup, it is also a renewable resource. These cane fields surrounding the plant are thus the rough equivalent to bottomless oil wells.

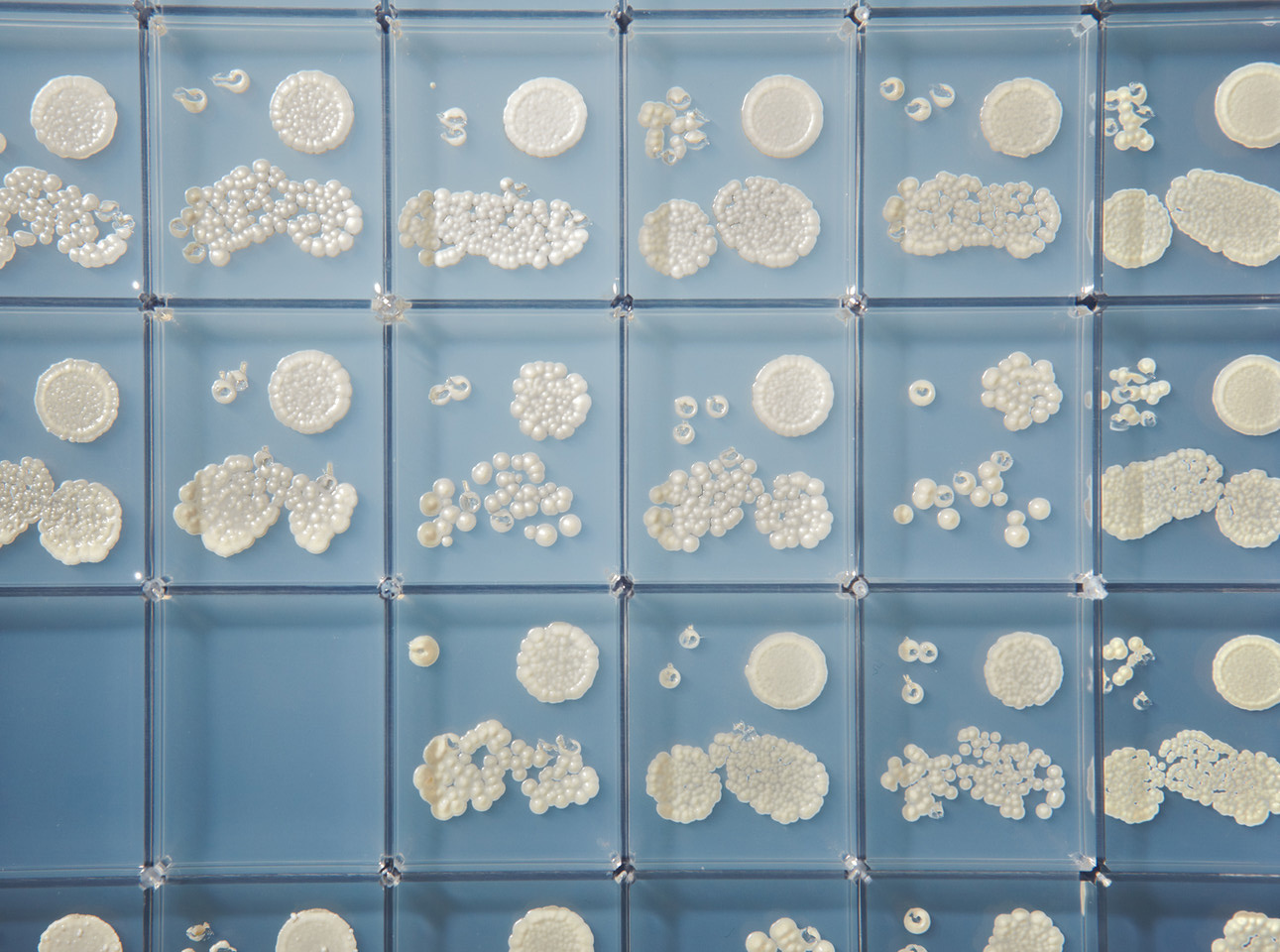

Amyris’s great innovation is deep inside the genetically modified yeast that chews up the Brazilian sugarcane. The yeast serves as a host for a set of DNA instructions--scientists call the organism a chassis, as if it were a simple platform, waiting for an engine. Depending on their goals, engineers at Amyris can outfit the yeast with a variety of genetic material that tells the yeast how to digest what it is fed. The result is a cell that can (at least in theory) ingest simple sugars and produce virtually anything. Indeed, if the yeast cells work as they’re supposed to, they promise not merely to change the energy industry by producing farnesene. They may also be programmed to transform the way many commodity materials are made. The first step would be petroleum-type materials. Rubber, chemicals, and medicines would follow.

At least that’s the idea. Already, in the short lifetime of the biofuels business, Amyris has become legendary--a stand-in for the sector’s breathtaking promise and now for its troubling descent. The company’s Brazilian plant is referred to as Paraiso, Portuguese for "paradise." It could be more aptly described as a grande esperanca, a great hope. Just a year ago, Amyris’s stock price soared to $33 a share. More recently, as the company reported $95 million in losses last quarter, it has plummeted to as low as $1.52. Meanwhile, a once-grand expansion plan has been scaled back. A plant at Sao Martinho, double the size of Paraiso, sits half-complete, vacant as of February. Amyris suspended production at another plant this year.

Everything now rides on success at Paraiso. This summer, as the final bolts were tightened and the last pipes sealed, Loosli readied himself to take command and find out what the plant can do. The future has become a matter of simple economics. If Amyris can produce farnesene efficiently here, the company will gain precious time to perfect its genetic technology. And if not? Then Amyris will likely capsize and pull an entire sector--an entire vision of the future--down with it.

A few weeks before I travel to Brazil to see the Paraiso plant, I discuss Amyris’s perilous situation with one of its founders, chief technology officer Neil Renninger. We meet at the company’s Emeryville, California, headquarters, in a small lounge decorated with black-and-white photos of Red Sox players and filled with comfortable leather couches. He reminisces about growing up in California--his dad had worked as an engineer at Intel, his mom as a schoolteacher. As he speaks, his slender fingers sometimes search for his iPhone, sometimes hang in the air, and sometimes touch tip-to-tip as he considers a thought.

Circles of exhaustion rim his eyes. His company is ailing and he wears it on his face. Just before my visit, Amyris had announced it had produced a million liters of farnesene in 2011, rather than the 6 million it promised. Its executives declared they would no longer make predictions about future production. "I’d be lying to you if I said that I didn’t look at the stock price," Renninger admits.