Scientists in Shanghai are working to revive a long-abandoned branch of nuclear technology: molten-salt reactors powered by thorium instead of uranium. Backed by the Chinese Academy of Sciences, the program has a $350 million budget, top-level political support and direct technical input from Oak Ridge National Laboratory in the United States—the same institution that pioneered molten-salt reactors in the 1960s.

Thorium appeals to both Chinese and American researchers because it promises safer, cleaner and more efficient reactors. Instead of high-pressure water systems, China’s design uses molten salts, reducing risks of meltdown and avoiding the long-lived waste produced by uranium cycles. If successful, proponents say, the technology could dramatically reshape global nuclear energy.

China’s push has unusual diplomatic dynamics. Despite rising strategic rivalry, U.S. officials have raised little objection to Oak Ridge’s cooperation with Chinese scientists. Much of the original thorium research is already public, and some American experts see China’s work as a chance to advance a field that the U.S. largely abandoned decades ago.

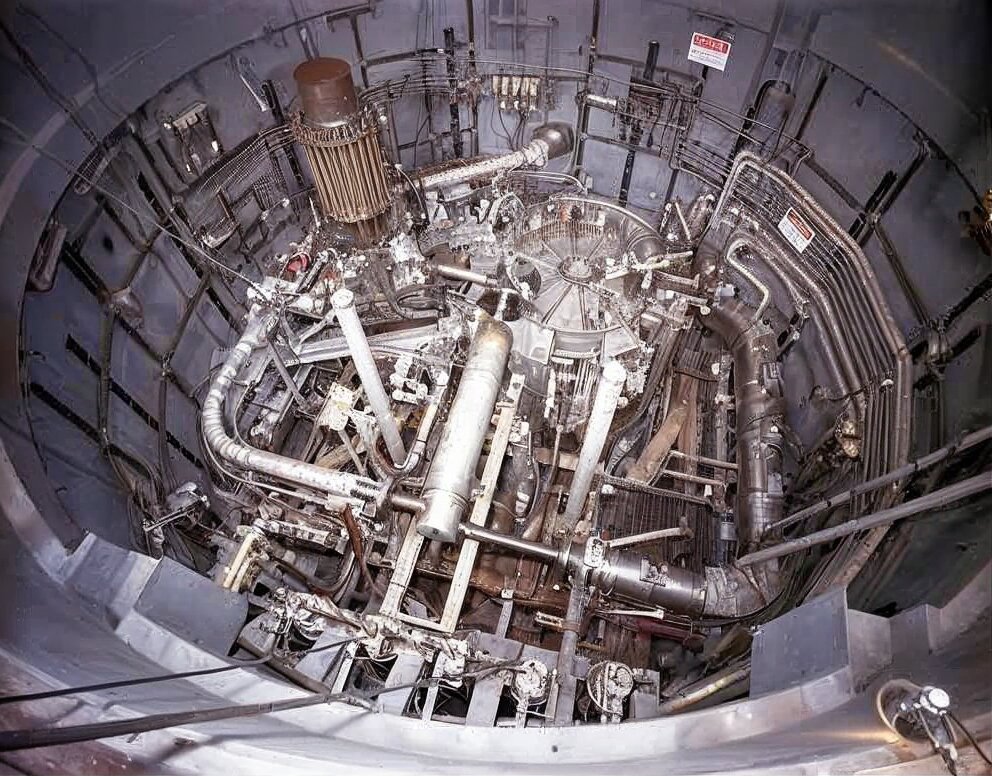

The Chinese effort reflects an attempt to return to ideas demonstrated at Oak Ridge in the 1960s, when a molten-salt reactor using thorium-derived fuel ran safely for several years before being cancelled. At the time, the U.S. military and civilian nuclear sectors chose uranium technology instead—partly because it produced plutonium for weapons.

Thorium itself cannot produce weapons-ready material easily, though the fuel can support naval propulsion or remote power systems. China’s navy, which has struggled with reactor performance in some submarines, is watching thorium closely. British engineers have also proposed thorium reactors for future warships.

Jiang Mianheng, son of former Chinese president Jiang Zemin, is driving the program. After visiting Oak Ridge in 2010, he secured a cooperation agreement that provides China access to historic design data and ongoing scientific exchange. A formal protocol with the U.S. Department of Energy specifies peaceful use and open publication of research results.

The Shanghai Institute of Applied Physics is rapidly expanding its thorium team, aiming for 1,000 researchers as it builds stepwise demonstration reactors through the 2020s and 2030s. China’s nuclear industry is already aligning behind the project, with state-owned companies preparing to supply thorium and molten-salt materials.

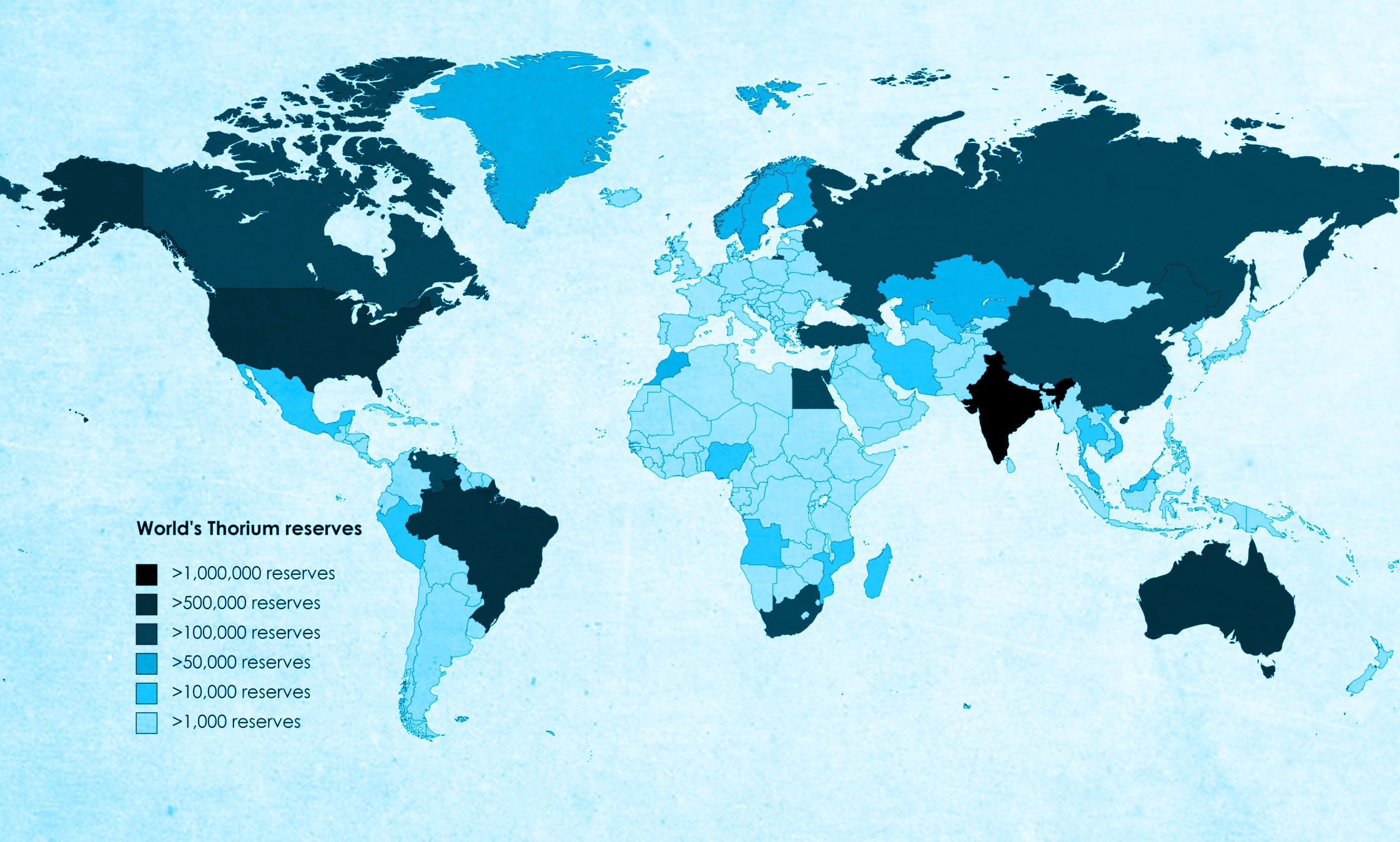

Thorium fits neatly into China’s broader energy strategy. Coal still supplies about 80 percent of the country’s power, and Beijing wants rapid expansion of cleaner alternatives. Alongside dozens of new uranium reactors, China views thorium as a long-term hedge—especially given its large thorium reserves and limited domestic uranium.

The ultimate goal is commercial deployment around 2040. If the effort succeeds, China could be the first nation to transform thorium from a promising experiment into a practical source of safe, abundant, low-carbon power—a technological leap Jiang likens to “being the first to eat a crab,” taking the risks required to discover something new.