One of the leaders of the MSRP effort was Paul Haubenreich, who was the co-author along with Dick Engel of the journal article “Experience with the Molten-Salt Reactor Experiment” in February 1970. Mr. Haubenreich is a WWII veteran and graduated from the University of Tennessee and the Oak Ridge School of Reactor Technology (ORSORT). Mr. Haubenreich worked on the earlier Homogeneous Reactor Experiment-2 (an aqueous homogenous reactor) and then went on to supervise the construction and operation of the Molten-Salt Reactor Experiment (MSRE).

Sorensen: Please tell me what you just said, about shutting down the Molten Salt Reactor Experiment:

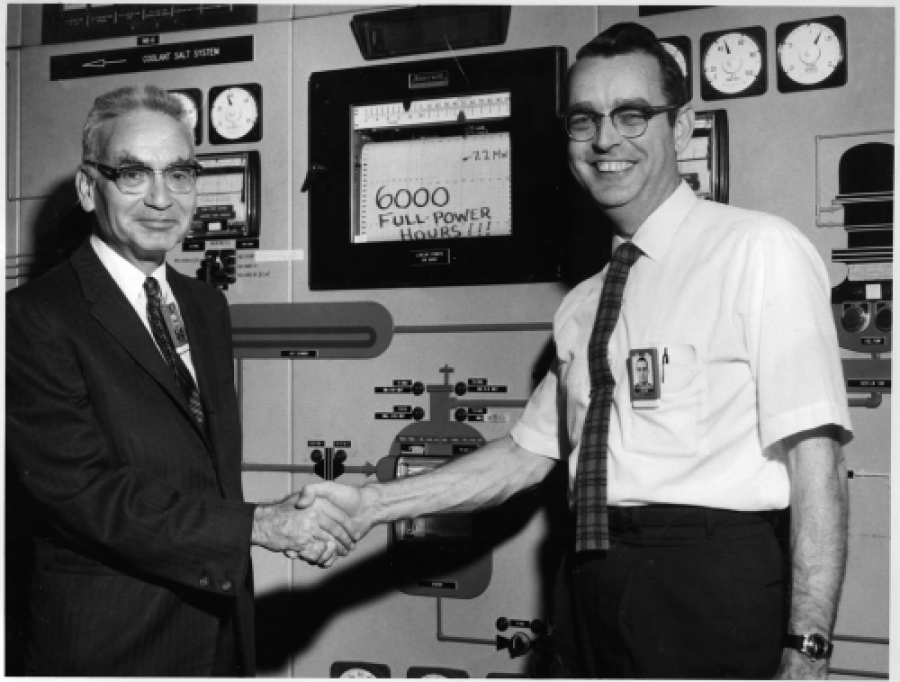

Haubenreich: OK, my recollection is that we had been told that we would have to shut the reactor down in 1969, by the end of 1969, and by the way, the reason that we heard was from an old classmate of mine, Milton Shaw, who was head of reactor development in Washington. He was an enthusiast for the fast breeder reactor. The way I got the story … he called up Alvin Weinberg and says “stop that reactor experiment…MSRE…fire everybody, just tell them to clear out their desks and go home, and send me the money!” Weinberg says “Milt, if we do what you say, you’re going to have to send us more money because we have contracts to pay everybody off, the termination allowances are not in this year’s budget”. And so anyway, the bottom line was that we had to shut down around the end of 1969. We had been together for five years, the crew had, operations, analysis, and maintenance sections. The reactor had first gone critical in June of 1965 and from that time…sometime earlier in ‘65 to late in ‘69 we had kept it hot, salt molten, with around the clock coverage, three shift coverage, 24 hours a day. As the end approached, and the curtain had to come down, it occurred to some of us it might be a nice thing to do to let everybody go home for Christmas. Up to that time we had kept people operating Thanksgiving, Christmas, every Easter weekend and everything else. So, that sounded like a good idea and I said “we have to get this place secured before we can close the door and take the day off”. So everybody agreed to that, we put the salt in the storage tanks and by Christmas day we said “everybody go home, have a good holiday, come back, we’ll see if there’s anything else we need to do”. And that’s what happened, that is my recollection of it, and I guess that’s pretty accurate. We didn’t mean for it to end that way. We had a facility there that we could strip the uranium out of the salt, and had done so with the first charge in which partially enriched U-235 was our fuel for the first… what? 4 years? no, 3 years. And then we loaded in U-233. U-233 had never been used, it had been discovered by Ray Stoughton and Glenn Seaborg –yeah, the chairman of the Atomic Energy Commission at that time, Glenn Seaborg out in California. We stripped the U-235 and U-238 out and put the U-233. The volatility process did not remove plutonium, so we had a smacking of plutonium in the salt at the time, at the last period of operation. This is all very interesting from the dynamics reactor

Paul Haubenreich: Anyway, if you don’t register you can take notes. Anyway, there were 40 of us at Oak Ridge who constituted the student body of the Oak Ridge School of Reactor Technology [ORSORT] and we were enrolled in a program to last twelve months. I don’t know why that’s interesting but — oh yeah, twenty of the forty were new graduates like me, twenty were from the Navy and Milt Shaw had been working for [Admiral Hyman] Rickover and the Navy, we had people from the Electric Boat Company that were overseeing the Nautilus reactor submarine, and from General Electric, Westinghouse, all these people. Twenty of them and twenty recent graduates. Shaw and I were among the forty students in the Reactor Technology. He was a little older and had had the experience with the Navy and I was first-out-of-school and the twenty who were new graduates had the option at the end of their year of ORSORT…they were free agents. Because of the jobs situation and all, each of us got several offers and I was the only one of the twenty that opted to stay at ORNL [Oak Ridge National Laboratory] and a couple of others straggled back later but Shaw went back to Washington and I stayed at ORNL on the Aqueous Homogeneous Reactor Experiment and then with…in 1964 they organized a department at ORNL to do the operations and analysis of the Molten Salt Reactor Experiment [MSRE]. We trained and practiced for the better part of a year and the criticality was achieved during June the first of ‘65. And I guess… when was it? oh!, part of the reason why I was tapped to be the manager of that department was that I had meanwhile turned into a nuclear engineer. I had that year of ORSORT and when the ORNL wanted its engineers to do the Tennessee Professional Engineering Exams, get the PE after their name, I was grandfathered for the Basic Engineering, didn’t have to take that. They said “what branch of engineering do you want to take the test in? You’ve got a bachelors and masters in mechanical engineering” and I said “yeah, but I have the ORSORT stuff so I believe I’ll take it in nuclear engineering”. Well, in the lull between aqueous homogeneous and molten salt UT [University of Tennessee] Knoxville said “we want a Nuclear Engineering department”. My advisor on my Masters in mechanical was Pete Pasqua. He said “I don’t know anything about Nuclear Engineering” they named him to be the head of the department…

Sorensen in the background: was he whom the Pasqua building is named after?

Haubenreich: Yeah.

Sorensen: Ok, yeah

Haubenreich: Pete Pasqua. He jumped down to UT from Purdue, just a few years before being my advisor on my Masters thesis. But he came to me and said “can you come up with a curriculum for graduate students in Nuclear Engineering?”, well, yeah, I guess I could, so I had all of my textbooks from ORSORT and knew the people at Oak Ridge and was working out there, so I came up with a one year course in Basic Nuclear Engineering using Glasstone and Edlund

Haubenreich: When I took the [professional engineering] exam at Knoxville, the written exam, I didn’t have much trouble, because I had taught that graduate course in nuclear engineering. And when I went down to Nashville for the oral, they said “Mr. Haubenreich, we have a question: did you see these questions before you took the exam?”

Sorensen laughs hard on the background

Haubenreich: I said “well, in a sense yes”. They said “yes!?” I said “well I taught this course and every one of these questions on your exam are what I gave my students. [Sorensen laughs again] I would’ve been disgraced if I didn’t ace this exam”, which they said “you did!”, I had a perfect score. So anyway that helped to get me the job of managing the Molten Salt Reactor Experiment. But I had some very able people. And I will tell you another little sideline: the operation of the MSRE was not too difficult…wasn’t too burdened with problems…but there’s some. And the people that I had working for me, that was in the 1960s, had grown up, most of them, in East Tennessee, and one of the things they all had besides hound dogs under the porch were old cars out in the yard that didn’t run very well. And every one of these country boys had to learn how to raise the hood and get…uh…fix things. And when 10 or 15 years later they were assigned to the Molten Salt Reactor, if anything came up… we cut the rope on the windlass one time, I’ll tell you about that if you wanna hear it Sorensen agrees] for sampling and feeding fuel in and… and I said “Oh my goodness, we’re out of business” and they said “we can fix that!” and I said “how are you going to do it” and they said “I don’t know but we will fix it!”, and they did! Several things happened like the time the skunk went to sleep in the trash can and they got him out without having to fumigate the place…a lot of fun things happened. We had a good…well organized… we had a fun time. I went deer hunting a couple of years with my technicians who operated the facility in… so we were almost family, I think. So, it grieved me when at the end of the operation we had to tell some of the people: “we don’t have a job for you anymore”. But that was the way it was.

Sorensen: Can you tell me a little more about Milt Shaw and why it was he instructed them to shut down the experiment?.

Haubenreich: Milton Shaw was sold on the sodium-cooled fast reactor…breeder reactors. And I am not familiar with his… why that was. At the time he was working for Rickover, the Navy was still pursuing the sodium-cooled reactor which went in the Seawolf submarine [SSN 575, not the modern SSN 21] and the pressurized-water reactor that went into the Nautilus. And so, by the late 60s Milt Shaw still had it in his mind that the sodium-cooled reactor which was the type of reactor EBR-I (Experimental Breeder Reactor I) out at Idaho was still viable. But it needed more money to develop it, and so he said “well we can get some money from shutting the Molten Salt Program down”, and as far as I know, that was his idea. But that was a true story I said that Shaw told Weinberg “you gonna have to shut the Molten Salt down and give me some more money for fast breeders”. And the fast breeder persisted for quite a while, as you know…

Sorensen: The money that they were spending on the MSRE, I’ve seen the budget, what they spent on the sodium versus what they spent on molten salt, and the molten salt was a little tiny fraction…

Haubenreich: Oh, yeah, yeah, we were minor-league, money-wise compared to some of the other programs. So we realized that. And I won’t say that the penny-pinching affected our operation any, but it did, we wanted to strip the uranium out and put it back in the hot cell over the next in(?) and do something about the salt where the fission products remained, and they said “well, here’s what you do: Everybody go home, but once a year go by you can heat the salt up and let the [ Sorensen interjects: “fluorine recombine?” ] radiation damage to the frozen salt heal itself. And next year we’re going to have a permanent waste facility in New Mexico”…that was before Yucca Mountain was conceived [the waste disposal proposal to bury at Yucca Mountain long term decaying radioactive waste]. and they said: “We will just take that salt out there to New Mexico and bury it in the salt, in a sodium chloride salt dome and that’ll be a good enough place for it,” that was in ‘69, and we don’t have it yet!. So anyways, the upshot was that “chemical transuranics, you’re redundant, we don’t need you, we’re not going to strip the fission products, we are not going to strip the uranium out of the salt and ship the salt with the fission products to a storage facility” and that’s the way it went. So we were, you might say, forced back into the dugout, shutdown, the game was over, Christmas ‘69.

Sorensen: So, the program continued for a few more years after that.

Haubenreich: Yes it did, and Rosenthal was the director of the Molten Salt Reactor…they gave me a post as assistant director or something like that and I did a lot of spare time work on nuclear safety journal, and the environmental impact statement for Duke’s Oconee plant but three years, in the spring of ‘73, the fusion program needed somebody and so Weinberg told me “you have your pick, you can stay in the fission reactor with Paul Kasten on the gas-cooled reactor, or you can go to fusion”. I thought about it, prayed about it, Mary and I did, and we said I am going to stay with something I know something about…in the fission [program]. A few days after that, Floyd Cutler, who was the associate lab director came in and said “I need to talk to you in private”, and I said “come in Floyd” and he said: “I know we told you you had a choice, but you made the wrong the choice!” [Sorensen laughs] “and I am here to tell you why fusion is better”, he convinced me and I went to fusion. Of course that was a good move. I spent the rest of my… how many years? ‘73 to ‘91 in fusion. But they said “you know how to work with people” and I said “I don’t know anything about…”